Crisis of the Carol Christian Poell object

On Carol Christian Poell's loose marriage to Surrealist objects

It’s been a while since I actually wrote about fashion. After all, if I remember correctly, this blog was created for the sole purpose of analyzing runway shows and, in more ways than one, a sort of encouragement for my continuing autodidactism. But now, obviously, the whims and wanes of life have made it so I’ve pretty much neglected this mission altogether, and instead I’ve been drawn this way and that, away from the institution of fashion analysis and toward the humiliating oasis of middling college student and “Substack blogger” (my attempt at buttoning up my collar to the throat and becoming a Sontag-like figure in my own razed imagination.)

But like a chip of paprika lodged in your cheek, the stinging “monde de la mode” never left my mind, and every now and again I’d cough up some of its remnants into my lap and wonder: what the hell am I doing here? So, dear imaginary Substack reader, today I become a teenager again and return to my roots…

A show which has always struck a Stendhalien chord is Carol Christian Poell’s SS04 collection “Mainstream Downstream.” Like any asshole “archive fashion” kid who thinks they're smart for no reason, once I graduated from the fashion prolegomenon of Rick Owens and began daydreaming about attending Central Saint Martins, the only logical next step was to dip my toe into the waters of Milan. Carol Christian Poell (CCP) has always been a bit more cerebral than its avant-garde contemporaries (which is saying a lot, considering a high-level of headiness is practically required for any “avant-garde” worth their salt), venturing closer to performance art territory than the flat-out commercial theater of conventional runway shows. I’ve always felt CCP garments were destined to be exhibited in modern art museums rather than placed on racks in a showroom, however, the fact this isn’t the case isn’t necessarily negative. Any good fashion label ought to position itself at the nexus between pure art and commerce (are you listening Instagram streetwear brands?), it just so happens CCP leaned more toward one than the other.

One need not look far for evidence of CCP’s avant-garde qualities than their literal website: an all-black webpage save for the thin white lettering of “Carol Christian Poell”, along with links to bunch of legal stuff and a business email, in case you were hungry to start a correspondence with their intern. A colorless ether, the frozen lake Cocytus in the ninth circle of Hell, a polar bear in a snowstorm, Ad Reinhardt, the dusty aftermath of an imploded star — bereft of information or the desperate aches of showiness. You don’t end up here by accident. The clandestine nature of this website is what I assume to be both an attempt at intrigue as well as a symbol of exclusivity. And in case you were curious, the CCP Instagram is just as mysterious – a private account, with a little over 6,000 disciples… ahem …followers, worshipping the leather knee of their Austrian fashion messiah.

I guess in some way, CCP’s insistence on maintaining its privacy (and for all intents and purposes, appearing defunct) makes the independent label’s legacy all the more meaningful in an age where fashion conglomerates command the market and creative landscape (even Martin Margiela and Helmut Lang, both successful avant-garde designers in their own right, left their respectives houses in the early 00’s to become full-time artists: the age of avant-garde fashion is dead!)

Even so, CCP is a label managing to survive on the surface: its name only kept alive by users on fashion forums or the webpages of second-hand retail sites (it’s been something like 15 years since Poell came out with a collection. Damn Carol.) Step outside the screen and trust me, you will never, ever, see CCP out in the wild… or, at least, the chances are quite slim. And why (may you ask)? Well, because CCP garments are not designed to be worn so much as to be gawked at (and also partly because CCP pieces are coveted as fetish objects by menswear-obsessed freaks). That being said, this is exactly why they are loved.

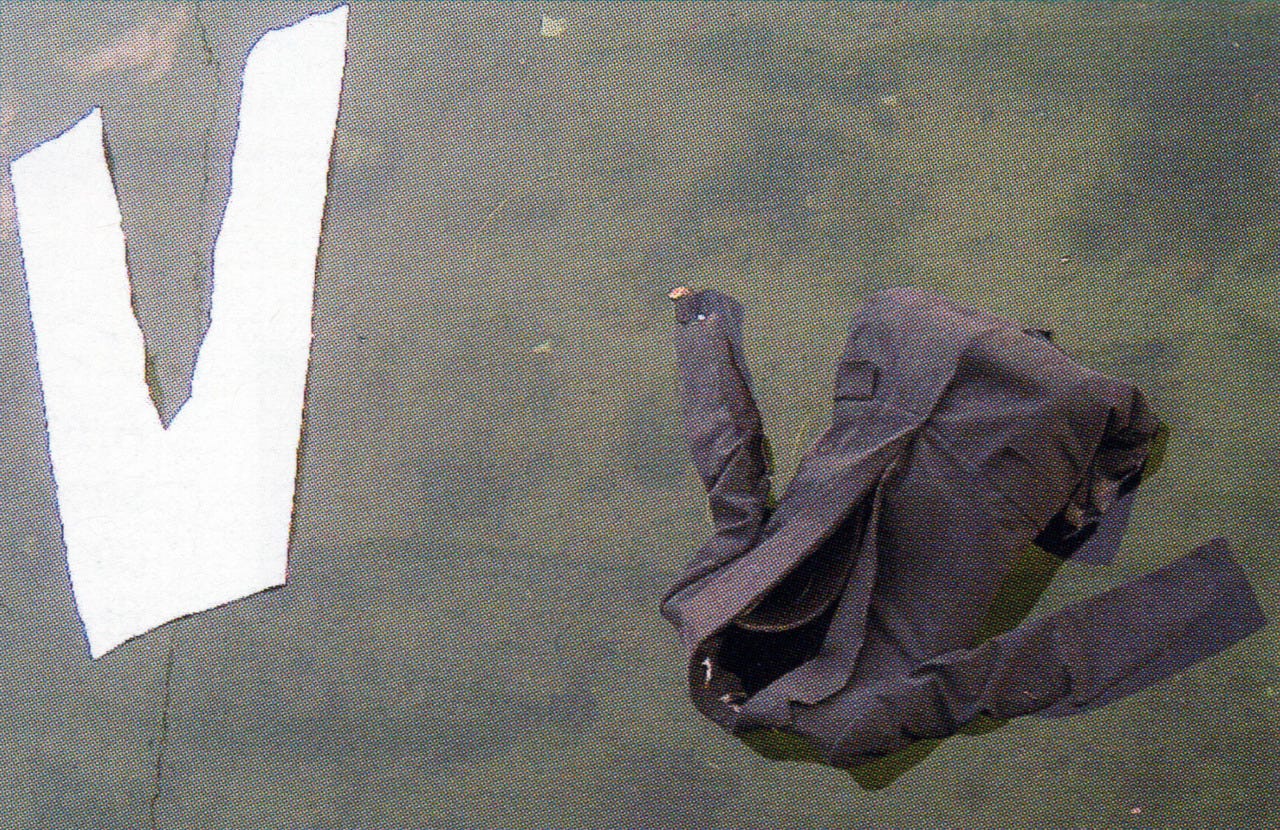

Poell arrived at the name for his SS04 collection in a typical avant-garde way, that is, as a statement of rebellion. The “Mainstream Downstream” show itself presented a striking picture of limp, supine models floating down the (probably fetid) Naviglio Grande canal in Milan. It’s hard to ignore the way in which these models recall a mad Ophelia surrounded by garlands, dead in the water after drowning herself. Fashion victims, victims of fashion. Hemorrhaging love of the game. Assuming these models are dead bodies, is the whole industry of “mainstream” fashion, then, nothing but a bloated corpse subject to forces beyond its control, made to float thoughtlessly and aimlessly downstream, wherever the current decides? These are themes Poell seems to imply in the name of the show — perhaps he too understood the avant-garde as a once-spry creature now long-dead, and the stinking water of the canal merely a reflection of its steaming carcass. Progress is only possible by going against the stream. Did Poell mean for this show to be an epitaph to the avant-garde? A needed farewell? I dunno, but that’s my interpretation. Nevertheless, whatever the exact intended meaning, it remains undeniable that the imagery of models floating there, as if under some sleeping spell or playing dead, is completely arresting, and of course, the show’s most raved-about image (plus a beloved profile picture for fashion boys everywhere.)

Outside of “Mainstream Downstream”, it’s funny how similarly Poell’s other work echoes that of the Surrealists. And I don’t mean to draw indecent parallels here. Poell is a trained craftsman and an expert in men’s and women’s tailoring, and is well known to work in various natural materials, notably leather. The sheer level of craftsmanship which is poured into a given CCP garment cannot be understated, however, how wearable are these items at the end of the day? I mentioned that CCP pieces, while lauded, are not purposefully treated as normal clothing. They are first and foremost objects. And this is by design.

Méret Oppenheim’s assisted-ready-made, “Le Déjeuner en fourrure” (1936), is one my personal favorite found object artworks. Here, Oppenheim transforms a regular cup and saucer into an erotic, discomforting Surrealist sculpture through the application of Chinese gazelle fur (rumor has it this idea was spurred on by a conversation the 23-year-old Oppenheim had with Picasso and his then-wife Dora Maar). The use of natural material here gives sculptural form to the objet trouvé (that is, the fur is the form and without it, there would be no sculpture), assaulting the viewer with subconscious associations. What is so confronting about a fur-covered cup, and why am I both drawn to it and repulsed by it? Why is it both excessivley barbaric and also beautiful? Why do I want to both glide my tongue along it and also burn it?

But it’s not just the material quality of the artwork — its furriness — that represents the entirety of its meaning. This sculpture does not become a perverse object without the help of the viewer’s imagination, stimulated by the natural material of the sculpture — the piece assumes an “extra-plastic” (to use a Dalí-ism) quality dependent on the viewer’s psychological (or, as the Surrealists likely intended, psychosexual) response. In this way, the viewer’s reaction to that simple visual of fur on a cup, whether sickness or awe, is integral to the success of Oppenheim’s imagery.

There have been some attempts to give reason to the disquiet produced by Oppenheim’s sculpture, particularly by André Breton, founder of the Surrealist project, in his theory of the object. The logical underpinnings to the questions provoked by “Le Déjeuner en fourrure” are presented as a product of what Breton dubs, “the crisis of the object.” In a lecture delivered in Prague in March 1935, a year before the creation of Oppenheim’s fur-covered cup, Breton describes the Surrealist situation of the object, invoking Freud:

The only domain left for the artist to exploit became that of pure mental representation, such as it extends beyond that of true perception without for all that being identical with the hallucinatory domain … The important thing is that recourse to mental representation (outside of the physical presence of the object) furnishes, as Freud has said, "sensations related to processes unfolding in the most diverse, and even the deepest layers of the psychic mechanism.”

Here, it’s quite clear that the aim of the Surrealist object was to bring forth, as Dalí called it, “phantom” associations buried deep within the subconscious in a violent, rapturous way, because man’s relationship to perception and representation is so often a violent one. Incidentally, the principal way in which the Surrealists aimed to reconcile this relationship was through the introduction of dreams into the subject matter of art. Dreams, for the Surrealists, are like the Greek ferryman Charon, serving as a guide to access the hidden nature of one’s interior world — to grasp, finally, and wrest away the blinding reality principle that bars us from understanding our own psychic machinations.

It’s this squishy, vulnerable interval between objective representations of reality and the subjective perception of dreams that the Surrealists are daring to pinch and digest. At the very least, this is one of the main tenets of Breton’s Surrealism: to escape the web of present reality. With the disparagement of present reality comes the disparagement of conventionality, and abracadabra, so follows the avant-garde. Thus, Surrealist objects are not merely sculptures, they are also conceptual artifacts bound to a myriad of psychic associations.

Carol Christian Poell’s designs are no different (aha! — almost forgot we were talking about CCP, weren’t you?)

I hesitate to call CCP’s more conceptual works pure art objects, but in truth, the spirit of their design is so in line with the Surrealists that I cannot help but create strong connections between the two in my mind. As such, I’ll start by surveying a couple of the more classically provocative CCP concoctions and let you judge for yourself whether this connection holds up.

Onto the Carol carousel we go.

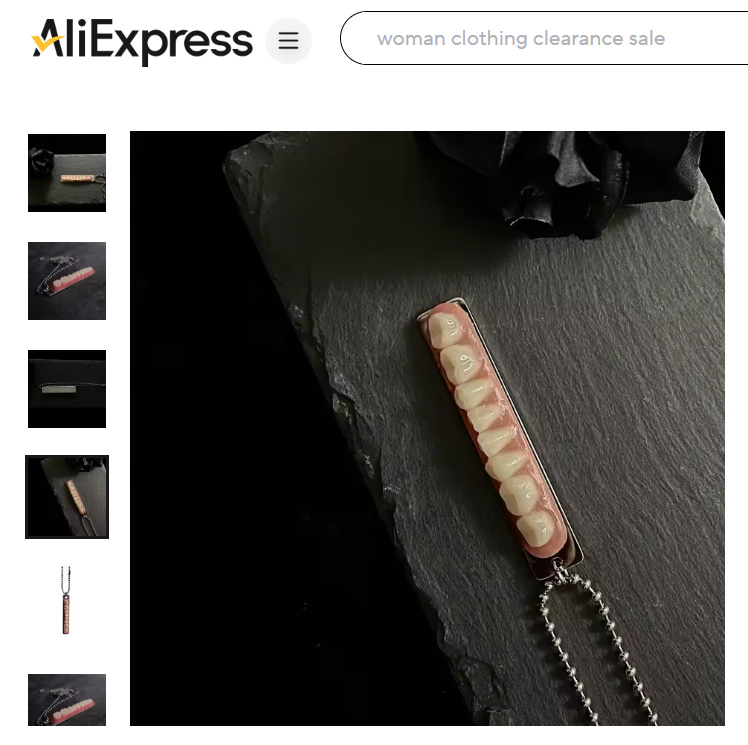

You’ll come to notice throughout most of Poell’s oeuvre recurring motifs centering the body. Even in “Mainstream Downstream” there clearly exists a concern with fashion’s relationship to the body as both a natural extension and innate part of it. Poell’s teeth necklace, as any ‘ccphead’ would let you know, is quintessentially CCP — Poell at his most shocking, at his most avant-garde. CCP’s teeth necklace features a silver pendant adorned with a row of prosthetic teeth definitely in the vein of an art object. Indeed, it seems to me the only thing categorizing the teeth necklace as “fashion” is its contingent wearability and utility as a garment, or in this case, piece of jewelry.

Poell, though placing greater importance on his role as a designer over that of an artist, inevitably produces work that resists classification as mere sartorial commodity and instead embraces the status of art object or sculpture. The functionality of the object is not its main priority here, as it becomes increasingly evident that the distinction made between artwork and clothing is predicated on the aesthetic intentions of the designer, not the way in which it can be wielded or interpreted by the wearer or consumer.

Sure, you can regard the teeth necklace as nothing but a necklace, or, you can regard it as Poell likely intended it to be regarded: as a conceptual artifact intent on blurring the relationship between commodity and art by means of provocation, not unlike the Surrealist object. As ostentatious as this may sound, the mystical thing about CCP is that both of these truths can exist at once, and it’s probably better off that they do (no matter how intent I am in dispelling this fact).

Yet — I must sorrowfully add — like any object marred with the stamp of commodity (as clothing is), Poell’s designs, too, remain ensnared in the market logic of exchange and inevitably subject to commodification, irregardless of how high-brow or avant-garde or shocking or downright perverse they seem to be; the stamp of commodification will always be accompanied by the absorption into a deathless cycle of consumption. See above: CCP teeth necklace dupe (or as some fashion consumers call it, in an effort to hide their shame with a more dignified word, replica) on AliExpress for the price of $44 plus potential lead/cadmium exposure.

Next up on the carousel is baby’s first Grail: the iconic CCP liquid rubber drip Tornado stompers. I imagine these have to be the most impractical yet gorgeously supple boots in the world, but I wouldn’t know because Life has played a cruel joke on me and refused to allow them anywhere near my immediate vicinity. No matter, I gawk from afar.

These boots recall the maws of a wild predator, salivating and bloodthirsty, a starving jaw unlocking. Indeed, what I find particularly interesting about the Tornado drip boots is Poell’s deliberate subversion of function. Beginning with an otherwise utilitarian base (sturdy footwear), Poell opts to remove its essential functional element to render it, yet again, into an inert art object by adding long, sensitive rubber drips to the soles of each boot. The garment ceases to be merely an item of dress and instead exists largely to be observed. These do remind me of Man Ray’s Dadaist (or some may say proto-Surrealist) readymade, “The Gift” (1921), which similarly took an otherwise functional object and rendered it impractical by way of artist manipulation. I must admit Man Ray’s sculpture looks awfully similar in form to Poell’s drip Tornado boots, with the tacks sticking out of the sole of the iron like dripping stalactites … is that a stretch?

Can you even walk with these boots on, though? Given they easily set you back over $2,000 alone (and we’re talking second-hand), it’s unlikely you’d want to risk wearing down their most striking feauture, so what else is there to do except not wear them? This is what many collectors resort to doing — just like that, the boots migrate from a shoe rack to a display case. But why would Poell do such a thing? Perhaps this design element was added to test the limit of both the consumer and his own craftsmanship? Or, more likely, to imbue the garment with the aura of a fetish object — an artifact no longer merely worn, but desired for its significance beyond utility. A cult object.

I won’t dare to suggest these unconventional garments are meant to represent something like a focused repressed desire, but I think it is worth it to investigate just why they produce so much cult-like hubbub.

Certainly, they are beautiful objects.

In 2018, a man suffered a heart attack after admiring Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus”, and many have attributed this incident to a case of Stendhal’s syndrome. Stendhal’s syndrome is defined as a somatic response to art or beauty, and in the most typical cases, characterized by strong physical symptoms such as hyperventilation, fainting, or loss of consciousness in response to viewing art. I doubt I’m being cynical when I say it’s quite rare anyone experiences Stendhal’s syndrome in response to contemporary art. I won’t even attempt to explicate why this may be, I can only assume contemporary art today is lacking in the transcendental Sublime which pierces the human heart as if done by God. Whatever rapture allows the human soul to overcome with paradisical emotion is not to be found in the crevices of the contemporary Chinatown gallery. Yet, there is another feeling, somewhat equivalent, that is supplanted in its stead: an overwhelming appreciation.

For the elite snobs among us, looking at the finely-made artisanal garments of Carol Christian Poell probably does conjure a feeling of awe. But for normal people, it just produces questions. Lots of questions. To provide answers to these questions of “why?” or “what?” is not in the interest of Poell, nor was it really in the interest of the Surrealists, who wanted the viewer to identify for themselves their own emotions as a result of looking upon an object, instead of being told by the object what to feel. You are yourself, stunningly yourself.

When all is said and done, what I see in the work of CCP is both the peak of avant-garde “anti-fashion” design, and also a mirror reflection of my own capacity to appreciate and understand the macabre and peer into myself to connect the nuptial bands between the known and the unfathomable, between art and commerce, between perception and representation, between the object and the desire. I’ll officiate the weddings.